Kyoko Takenaka: An Artist Expressing Their Experiences in the Spaces Between Binaries

Kyoko Takenaka’s love for art came in bits and pieces, and then, all at once.

Their journey began with music. “My name actually means vibrations of sound child,” Kyoko reveals. Their dad, a jazz musician, named Kyoko after what eventually became their shared passion. Growing up attending jam sessions and surrounded by music, Kyoko always knew they wanted music at the center of their life. However, it was their father who was a jazz musician, an absent and abusive figure in their family’s life, who named Kyoko, and Kyoko linked those two things early on in their childhood, thinking that art was a selfish thing to do. It’s been their life journey to reclaim the meaning of their name for themself.

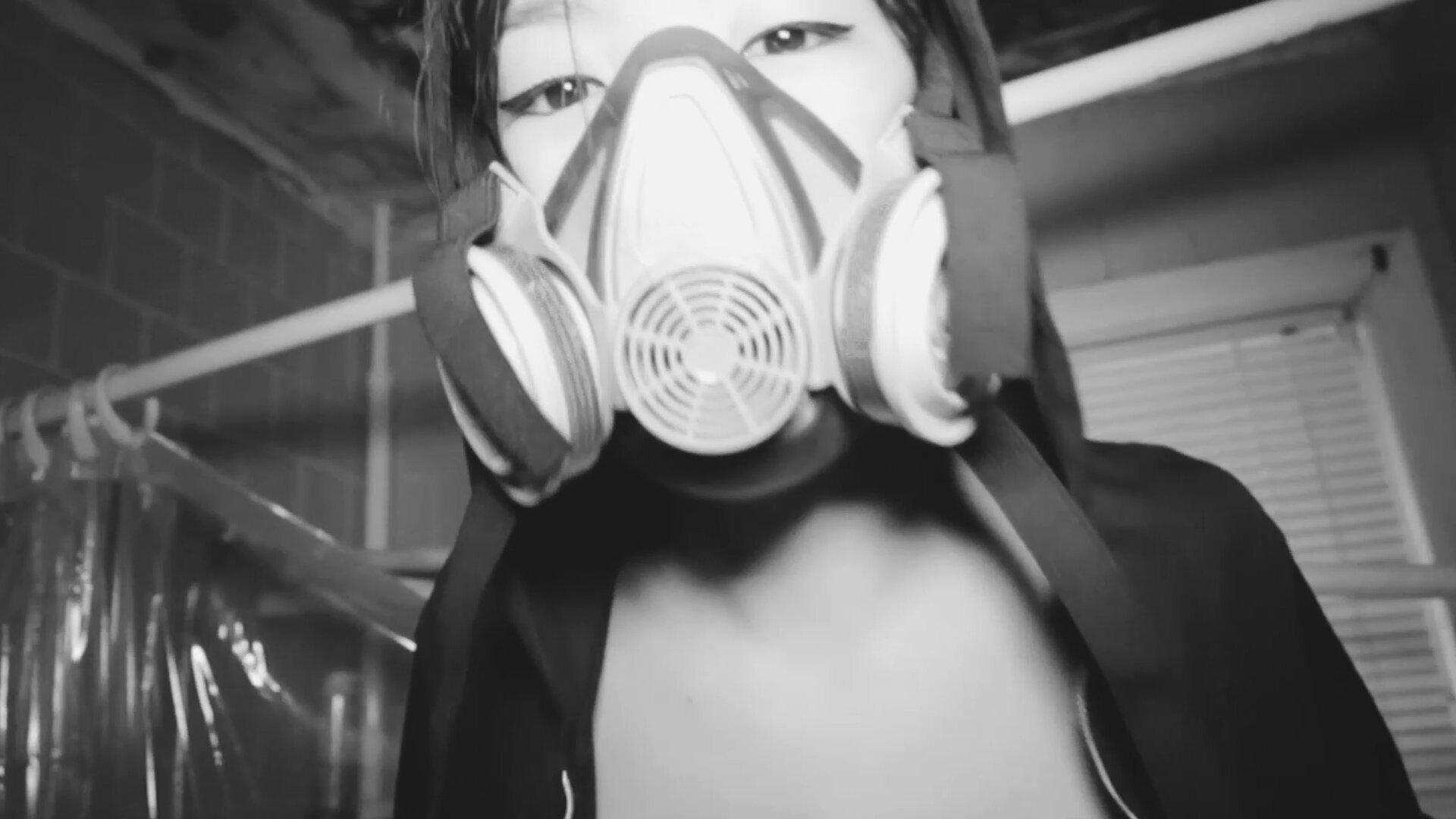

PHOTO by BRINSON BANKS

Expressing themselves through photography, on the other hand, came later on for Kyoko, and in a vastly different way. As they entered high school, Kyoko’s mother discovered she had breast cancer. “Photography was a way for me to both document and be present with everything that was happening during that time,” Kyoko recalls. This art form served as a gateway for Kyoko to explore different genres of visual media. As they fell further and further in love with the new perspective visual media brought, Kyoko chose to pursue photography and graphic design going into college.

Though Kyoko had always been artistically inclined, they found it difficult to picture themselves as an artist when they had never seen Asian American role models in the arts to look up to. They simply didn’t consider it a possibility. So while attending school, Kyoko pursued video journalism, utilizing their photography and videography skills in an internship with The Washington Post. While they focused primarily on film for the duration of their time at American University, Kyoko dove back into music following graduation.

While living in New York and pursuing music, Kyoko began to question the narrative that pursuing the arts is a selfish thing to do. They felt like they had the opportunity to express their voice and make an impact, and they wanted to take it. “I really thought about how I can incorporate everything that I do all at once and not be so hard on myself on dividing myself between different mediums of expression, whether that's music, filmmaking, photography, acting, directing, or movement. I think I thrive the best when I'm able to freely express and change between all those mediums,” Kyoko explains.

PHOTOS by JENNELLE FONG

Kyoko began with several moves, and as Kyoko’s locations shifted, new opportunities drew their attention. They lived in London, where they met close artistic collaborators and chosen family in the London QTIBPOC community, which eventually formed their queer Afro-Asia band, WASTEWOMXN. They moved to Los Angeles, where they concentrated on acting and modeling. They returned to New York, where they acted on the show High Fidelity as a punk teenager stealing from a record store. But in all their work, Kyoko searches for little ways to thread their passions together. “I really just tried to be a clear channel for whatever I’m called to do in that moment and through whatever medium,” Kyoko expresses. These intersections can be seen in their band’s art and its music’s feature on the soundtrack of their High Fidelity scene. Kyoko finds synchronicity in these moments, which is why they have grown to love medium overlap.

This love for an in-between space distinct from traditional social norms can be found everywhere in Kyoko’s life. “When I came out as non-binary, it was a moment for me when I realized how all of my identities could be linked in that expression of being non-binary. Being non-binary has allowed space for my cultural identity to be non-binary, as in not Asian or American, but somewhere in that unnameable space in between. As an artist, I think about being non-binary as well. I'm not just a musician or just a dancer, just a writer or an actor. My whole life is about being in that non-binary space and exploring what it means to be somewhere and expand the space of possibility for yourself,” Kyoko emphasizes.

Kyoko recalls that at the time they came out as non-binary, they were training in Butoh dance. This Japanese contemporary dance form emphasizes the concept of unnameable space, exploring the space between binaries, such as living and dead, animals and humans. Kyoko’s movement training with Hiroko Tamano included exercises such as transforming seamlessly between two opposing textures, such as a fluffy duvet to a gooey sewer. “I was dancing between binaries and embracing that unnameable space in between. Embodying non-binary as a verb, through movement and butoh specifically, allowed me to fully feel the liberation and belonging in that in-between space, ” Kyoko remembers.

PHOTO by JAS LIN

Like many Asians who grew up in America, Kyoko constantly felt as if they weren’t Asian enough for some things but too Asian for others. They felt alone in a space between. In their short film Home, Kyoko grapples with this in-between space through song, poetry, and documentation. They interweave audio recordings of racist encounters at bars with pop culture references to recount a story of alienation and a search for home and belonging.

As Kyoko found their identity, they wanted to see pieces of themself pour out of every piece of art they worked on. They feel as if they entered the Hollywood scene just as a push for both Asian American and nonbinary representation has swept through, though many institutions of the industry remain gendered. While this proves to be discouraging for nonbinary roles, Kyoko is optimistic and ready to fight. “I really embrace all parts of my gender expression. And to me, I wake up in the morning sometimes and take a long time really thinking about how my physical expression can match how I'm feeling that day. Acting is no different,” Kyoko emphasizes.

They continue to forge a space in Hollywood that has not yet been seen. Asian American nonbinary artists have such little precedent, and while this was discouraging for a young Kyoko searching for a path to pursue, they now see it as an open space that allows more expansive imaginations to come into fruition.

PHOTOS courtesy of KYOKO TAKENAKA

This lack of intersectional representation serves as a reminder that perceptions of gender and culture cannot be untethered from each other. Kyoko notes that while East Asians are often stereotyped as conservative when it comes to social issues such as the gender binary, queerness and nonbinary representation can be found throughout Asian history and art, such as in Kabuki theatre, wakashu, or nanshoku. Rather than the assumed inherent patriarchy of Asian culture, Kyoko notes that it was western imperialism that crushed the presence of queer and nonbinary representation in Asian countries. “It's really frustrating because that resurgence of opening [Asian communities] back up to LGBTQ+ issues often means opening back up to Westernized terms [and] adapting them to Asian cultures instead of finding our own language to express those things. These ideas were once so native to us,” Kyoko says. Kyoko felt this most heavily during their stay in Japan, where their perspectives on gender identity and sexuality are shaped so uniquely by their language and culture. In America, by contrast, forcing a white lens over the concept of queerness seems to be the only avenue through which Asian Americans can be reintroduced to these once familiar ideas.

“Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about how so much of my past work is based on my trauma and centered around whiteness,” Kyoko admits. They conveyed how struggling to depict concepts such as microaggressions and white saviors have been some of the greatest challenges in their art, not only because the topics are so complex but also because they have had to overcome so many fears in order to openly express their opinions on these issues. While Kyoko considers subject matters such as these core elements of their work, these issues are admittedly difficult for Kyoko to both express and consume. Kyoko hopes for greater Asian American representation that is not so deeply tied to anger and trauma, as it can become exhausting, especially for the artists creating these pieces. Kyoko is frustrated that Asian Americans cannot simply exist in the media; they must speak for an entire community’s experience with every project they pursue, while white people can play any role and focus on any abstract expression. Kyoko declares, “I want so badly [that] freedom and liberation for Asian Americans… [to] not just be seen when we're fetishized or expected to talk about our race, but to have control and autonomy over our visibility for all the ways that we shine.”

STORY JAMIE YI